Crypto scams surge in Israel as AI tech fuels sophisticated fraud

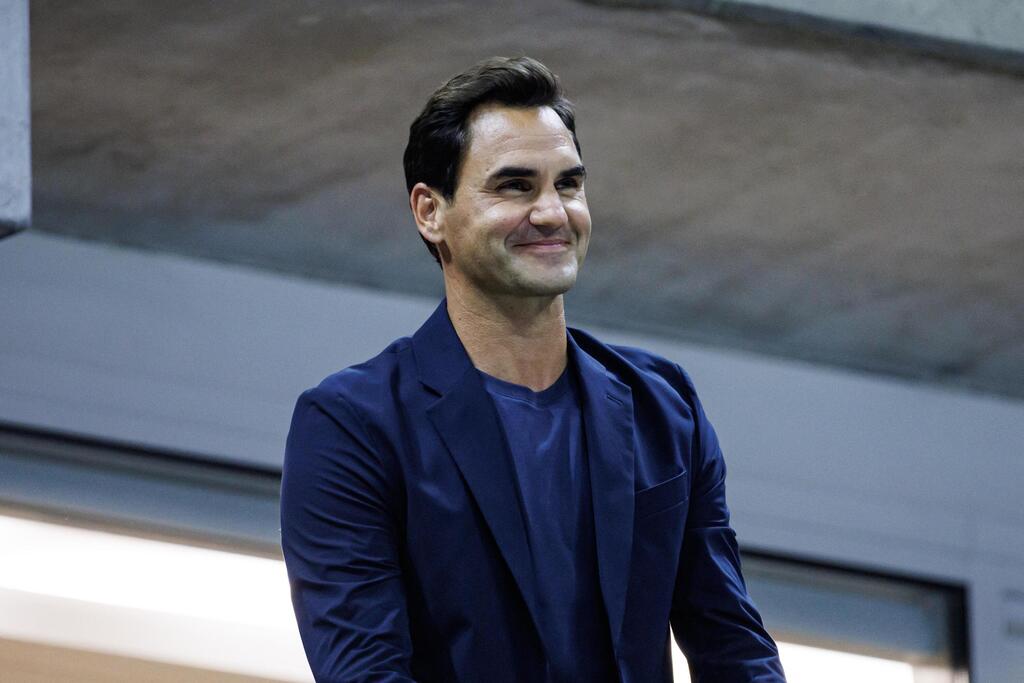

Roger Federer is considered one of the wealthiest tennis players in history. In addition to his $130 million in career prize winnings, he has endorsement deals with brands like Uniqlo, Rolex, Mercedes and Credit Suisse. His estimated net worth is around $600 million.

According to service staff, Israela explained that she and Federer had fallen in love and that he was planning a trip to Israel to meet her. The idea that she was being scammed didn’t cross her mind—until staff presented her with the harsh truth.

One of the more elaborate schemes involved the social media platform X (formerly Twitter), where fake videos circulated purporting to show CNBC anchor Maria Bartiromo interviewing U.S. President Donald Trump. In the doctored clip, Trump urges viewers to join a “$20 million crypto giveaway” allegedly in collaboration with Elon Musk.

Participants were directed to a link that led to a fake domain, where unsuspecting users were tricked into transferring their money. This was just one of dozens of scam domains—some registered through anonymous hosting services like Nicenic, which obscure ownership details and make enforcement difficult.

Avi Dayan, CEO and founder of Bitcoin Change, said another widespread tactic involves fake trading platforms. In these cases, victims are approached by a supposed “investment advisor” via social media. The scammer presents fake investment formulas and promises high returns, supported by fabricated success reports.

In the initial phase, the victim is asked to send a modest sum to a legitimate-looking crypto wallet tied to what appears to be a real exchange. After the first transfer, they are encouraged to invest more and shown seemingly profitable returns—until they attempt to withdraw their funds. At that point, they are told they must pay taxes to foreign authorities before the money can be released. But the money never arrives.

To add insult to injury, many victims are later contacted by a supposed attorney specializing in recovering lost crypto assets. The fee for these “services”? Just another part of the scam.

The tactics used by online scammers are evolving rapidly, with artificial intelligence now enabling the creation of near-perfect virtual personas that are difficult to distinguish from real people, cybersecurity experts warn.

“We’re witnessing a major shift in scammers’ methods. In the past, they relied on fake websites and edited photos—today, they use advanced AI technologies to generate virtual figures that look and sound exactly like the real thing,” said Yoav Keren, CEO of Israeli cyber firm BrandShield. “This poses a serious threat, making it harder for users to tell what’s real and what’s fake.”

Keren added that social media algorithms, which tend to favor content featuring familiar or intriguing personas, accelerate the spread of these scams—often without users bothering to verify their authenticity.

Dayan noted the challenge of waking victims from the illusion. “People just put money in without realizing the entire thing is one big fake. It’s very hard to snap them out of it. Because we operate a face-to-face service, we can speak to people and warn them. I see the person in front of me—for me, it’s not just another transaction.”

These scams have also contributed to growing public mistrust of crypto investments.

“We definitely sense this fear among customers. But there’s a big difference between putting your money into an exchange and keeping it in a private wallet. When your money is with a third party, the chances of being hacked are much higher than if it’s in your personal wallet. I’ve been in this business for eight years, and I’ve never seen a private mobile wallet get hacked.”

Yet Israel’s crypto challenges extend beyond trust. The industry remains hampered by the absence of clear regulations. There is no structured policy for crypto taxation, no legal framework for paying taxes in cryptocurrency, investing in crypto-based firms or granting crypto options to employees. Israeli banks largely refuse to support crypto transactions, and regulators—including the Bank of Israel, the Tax Authority and the Securities Authority—have yet to implement comprehensive rules.

Following a recent State Comptroller report revealing that the government is losing billions of shekels due to uncollected crypto taxes, the Tax Authority issued a draft bill proposing that crypto be defined as an asset, with profits subject to capital gains tax. The Finance Ministry also published draft regulations aimed at enabling taxation of entities trading in digital currencies.

Last month, the Knesset’s Subcommittee on Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Technologies held a discussion on the matter. Committee chair MK Orit Farkash-Hacohen, one of the few lawmakers actively pushing for crypto regulation, reminded participants that the previous government had formulated a policy to advance regulation. Two years later, however, government officials admitted that little to no progress has been made.

Nir Hirshman, CEO of the Israeli Crypto Companies Forum, warned that without regulation, blockchain firms are steadily leaving Israel, with a quarter of them no longer hiring locally. Yuval Roash, CEO of crypto trading platform Bits of Gold, shared the bureaucratic struggles his clients face with banks. Dayan added that he has been waiting seven years to receive a license from Israel’s Capital Markets Authority.

Israeli government officials appear aligned with banks in their cautious approach to cryptocurrency, citing concerns about money laundering and financial stability, even as hundreds of thousands of Israelis adopt digital currencies.

Ilanit Madmoni, head of the Fintech Innovation Unit at the Bank of Israel, said the primary concern for banks is the potential use of crypto trading for laundering illicit funds.

Hovav Elster from the Finance Ministry’s Chief Economist Division added, “It’s a matter of risk management. The collapse of crypto companies poses real risks to consumers.” As a result, the country’s tentative steps toward crypto regulation remain slow and fragmented.

Tracking the number of Israelis who hold crypto wallets remains inconsistent. According to the Bank of Israel, roughly 60,000 Israelis hold digital wallets, with assets estimated at $1.5 billion. However, the State Comptroller’s report cited a Finance Ministry estimate of 200,000 wallet holders, while the Tax Authority places the figure closer to 500,000.

At a recent Knesset hearing, Roash said his company alone has over 250,000 Israeli customers and estimated that the total number of wallet holders could be as high as 600,000. Whatever the figure, these are citizens the state can no longer ignore.

Bitcoin Change, Israel’s first crypto ATM network, launched in 2017, when Bitcoin was trading at around 7,000 shekels. Today, depending on market volatility and even statements from Donald Trump, that price hovers around 300,000 shekels.

The crypto market is extremely volatile. Do you feel it? How do people react to this volatility?

“Because we operate physical branches, we’re deeply in touch with the market. We see why people buy and sell. Some rush to sell when Bitcoin spikes. Others hear it’s rising in the news and come to buy.”

Why do people still buy crypto with cash instead of online?

“People still want a human touch. We serve seasoned users, not just beginners. Most of our clients also trade on exchanges like Binance. But Israeli credit card companies have blocked purchases from Binance, so people come to us with cash—up to 5,000 shekels per transaction—to deposit at our ATMs and fund their Binance accounts. And if someone made a good trade, they’re welcome to sell their crypto for cash right at the machine—no need to deal with banks.”

Banks often cite money laundering concerns. How do you address that?

“From day one, I set two rules: no anonymity—everyone must present valid ID. Second, we limit transactions to 10,000 shekels per day, 20,000 per week and 30,000 per month. No one’s walking in with suitcases of cash.”

Are you pressured to allow larger transactions?

“Of course. We reject dozens of requests daily. If someone’s looking to launder money—this is not the place. There are plenty of other venues, like Telegram. My rough estimate? Tens of millions of shekels move there daily in black-market deals. But there are scams nonstop—enough to fill an entire article.”