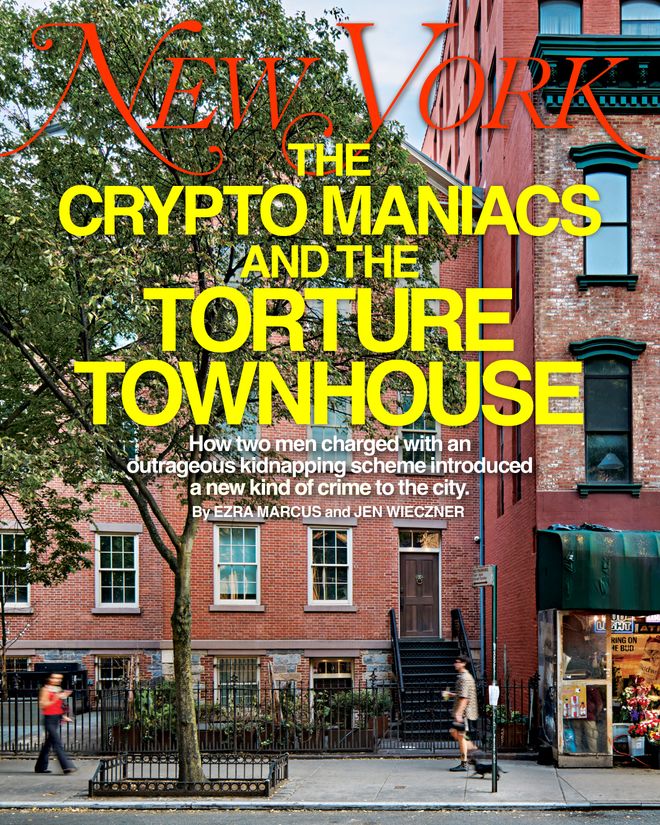

Crypto Investors Accused of Kidnapping in Soho Townhouse

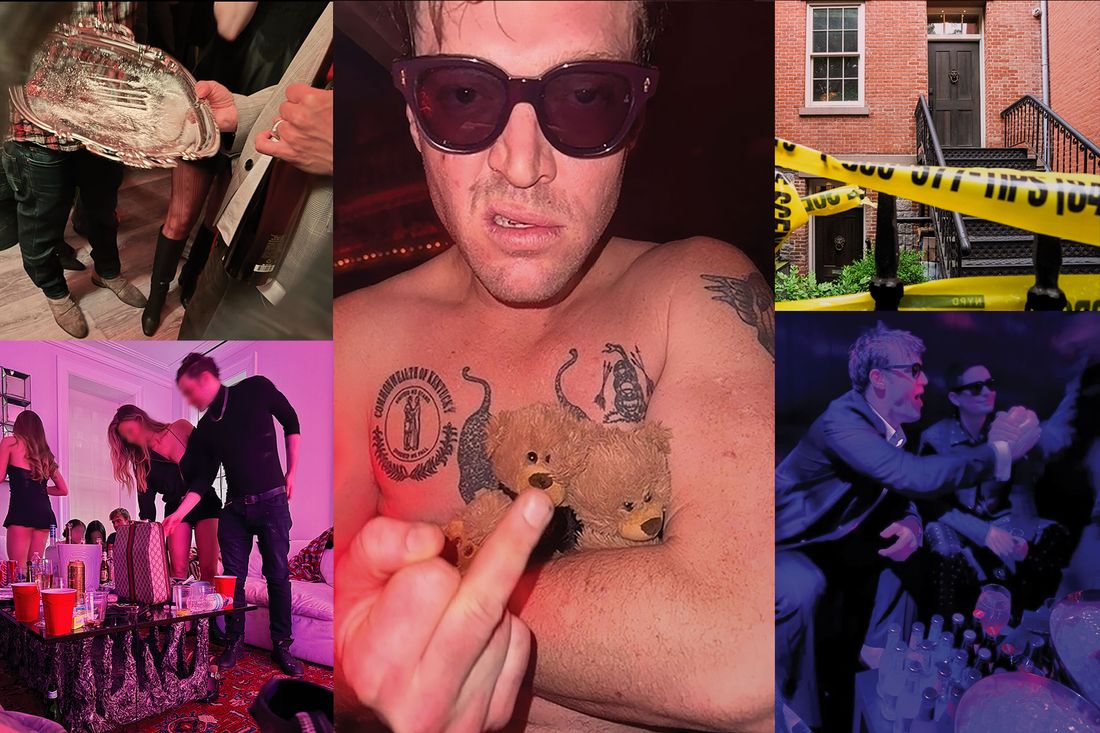

Photo-Illustration: New York Magazine; Photos: TMZ/Backgrid, David ‘Dee’ Delgado/Reuters

Earlier this year, word spread through the text chains of the insular group of men who own and operate high-end Manhattan nightclubs that two new whales had appeared on the scene. For months, William Duplessie and John Woeltz had been showing up nightly at clubs without a reservation. They were suddenly regulars at Jean’s, Paul’s Casablanca, and the Box, a downtown burlesque with a what-happens-here-stays-here reputation, where they often spent six figures in a single evening. Clubs had to scramble to find more expensive bottles to sell them.

They tended to bring their own security team — sometimes as many as ten guards, more than A-list celebrities have. Yet none of the nightclub operators knew who they were. Several people who saw them assumed they were tourists. “They looked like hillbillies in the middle of Manhattan,” one says, perhaps referring to the gun holsters they sometimes wore on their hips and their all-camo outfits. Other times, they wore Louis Vuitton monogrammed sets, or bear-fur vests, or bulletproof vests adorned with military patches. “When someone like these guys comes in, everyone gets all excited,” says a club promoter. “These are the types of people that nightlife is built on, because no rational-thinking person would do this on a regular basis.”

The party didn’t stop when the two got home. Woeltz and Duplessie transformed the five-story townhouse they were staying in on Prince Street into an after-hours nightclub of their own, filling it with young employees from Brandy Melville around the corner. The parties were wild and sometimes unnerving; the hosts bragged about ties to intelligence agencies and showed off guns, knives, and cattle prods. The same security team that accompanied them to clubs — some of them off-duty NYPD officers — patrolled the house at all hours.

This went on for months, until one morning, on the eve of Memorial Day weekend, when a 28-year-old man dashed from the townhouse onto the sidewalk, barefoot and bleeding from his head. He staggered down the street and flagged a traffic cop. He’d just escaped from a nightmare, he claimed in a lilting Italian accent. Two crypto investors had held him captive and tortured him for weeks for the passwords to his cryptocurrency accounts. The man, Michael Carturan, was taken to a hospital. Police soon arrested his alleged captors, Duplessie and Woeltz.

There have been at least 33 crypto kidnappings around the world this year; this would be the first known occurrence in New York. The appeal is irresistible. Over the past few years, as the value of crypto has ballooned, its millionaires and billionaires have lived heedlessly, some blithely filling the space left by mafia bosses and drug kingpins before them, publicly posting pictures of their Brickell penthouses and courtside Chrome Hearts outfits. These very suddenly, very flashily wealthy people have found themselves contending with the downsides of having chosen to release their fortunes from the grip of banks. Even the most successful crypto investors tend to hold their vast digital fortunes on their own devices, and their money can be taken from them almost instantly. All a thief needs is access to the right device, like a hard drive, or the password to an online account. Once a crypto fortune has been stolen, there is often no regulator or bank security department a victim can ask to reverse the transaction.

For some who knew Duplessie — friends, former business partners — his arrest seemed inevitable. In fact, some of these guessed he might be involved in the kidnapping before he was even named. “I just saw the headline, like, ‘Chain-Saw Torture in New York Penthouse,’ and I assumed it was Will,” says one former friend. “That’s how on brand it was for him.”

Michael Carturan in designer clothing Will Duplessie bought him. Footage obtained by WNBC showing Carturan approaching a Nolita traffic cop went viral. Photo: Gotham Galleria; Photo: WNBC.

Michael Carturan in designer clothing Will Duplessie bought him. Footage obtained by WNBC showing Carturan approaching a Nolita traffic cop went viral…

Michael Carturan in designer clothing Will Duplessie bought him. Footage obtained by WNBC showing Carturan approaching a Nolita traffic cop went viral. Photo: Gotham Galleria; Photo: WNBC.

William Duplessie grew up in Greenwich next door to the hedge-fund billionaire Ray Dalio. His father, James, was an investment manager specializing in distressed debt; his mother, Eve, was a social worker. They had four children but divorced when they were still young; James moved to a condo in Soho, and Eve stayed in Connecticut. Will, their eldest child, appeared to possess all of the privilege and pedigree that would guarantee future success. He was handsome and charming with straight white teeth, a chiseled jaw, and an enviable physique, not just tall but strong and hulking.

But from early in his teen years, he seemed unable to avoid trouble. His father told friends they’d “spent hundreds of thousands of dollars trying to figure out what was wrong with him.” Will told people that before he could finish his senior year at King, a private high school in nearby Stamford, he had stabbed a drug dealer.

After this incident, he later told people, his father shipped him off to China to work in a bicycle factory. There, each evening, Duplessie returned covered in soot to his five-star hotel. It seemed like a miracle when he was accepted to Bard College. He started in 2012 but showed little academic interest. He spent much of his time in a house off-campus his freshman year with Peter Brant Jr., son of the billionaire art collector. To people who met him, he came across as fratty, an anomaly at a liberal-arts school with no fraternities. “He never went to class, like, ever. I think he went to, like, two classes the entire time we knew him,” says a friend. Instead, he stayed home making electronic music — he DJ’d under the alias “William the Conqueror” and tried to get gigs at Webster Hall. “I don’t think anybody liked him, but they would all go to his parties,” says the friend. “He would buy a shit ton of liquor for everybody, and they would ball out.”

On weekends, Duplessie would escape to the city in his Audi, doing the nearly two-hour drive in a little more than an hour: “Just driving dangerously fast,” says the friend. He could be volatile. A perceived slight could send him screaming, his face ruddy and glistening with sweat and snot. “It was pretty terrifying to see, especially for someone that’s just so physically big,” says a former classmate. One night, as a show of toughness, Duplessie took a lit cigarette and held it to his own tongue for so long “that you could actually smell burnt flesh,” says a person who witnessed it.

When Duplessie was sober, he would heap praise on friends, offering to do them favors or make introductions. In this state, the former friend says, “he was an easy guy to like. He was fun to be around.” But by his second semester, Duplessie had dropped out.

He later enrolled at Tulane, his father’s alma mater. The friends he made off-campus, in the 13th Ward of New Orleans, weren’t like the gentle progressives upstate at Bard. He acquired a collection of guns. “I’m known as Wild Bill, and I’m feared in New Orleans,” Duplessie told friends. “I don’t wear blue because I’m Blood-affiliated.” Tulane students who knew him didn’t take any of it too seriously. “He would meet people along the way that had some attribute that he would say, ‘Oh, that’s cool,’ and he would integrate it into his personality,” says an old acquaintance. According to someone close to the family at the time, Duplessie had gotten mixed up in the local gang scene, apparently even agreeing to sell $5,000 worth of cocaine on one local syndicate’s behalf (and instead snorting it all himself). His father pulled him out of Tulane and brought him to California, where he was living.

One thing Duplessie actually had going for him was crypto. By 2017, he’d made enough off his early investments to open doors in the nascent industry. He managed to get a job in Los Angeles working for DNA, an investment firm focused on Web3 that was founded by Brock Pierce, and claimed he was making $100,000 a year. He lasted a month before he was “abruptly terminated,” says a person familiar with the situation. Duplessie quickly fell into debt, according to court documents and text messages from the time, sinking borrowed money into risky trades in the market and blowing it on cars he couldn’t afford. “Always had drugs, always had girls, never had money. That was Will,” says a former associate. By the beginning of October 2017, he was begging friends for money. “I’m in a bad spot,” he wrote to one, seeking what he insisted would be only a bridge loan until his refund check from Tulane came through. “Should I just sell my Rolex and buy another in a month or two?” he asked. He’d begun dating Joe Biden’s niece Caroline Biden — the relationship was turbulent and didn’t last long, friends say. “Will would buy very small amounts of cocaine repeatedly, all day long. He would just be like, ‘Hey, I just need to go say hi to my friend.’ And some car would pull up and then he’d have coke again. He would do that, like, ten times a day,” says the old acquaintance. At some point, the YouTube personality–slash–motivational speaker Tai Lopez supposedly paid Duplessie $20,000 to appear in a video with him. (Lopez didn’t respond to requests for comment.) A friend says he spent the same amount on drugs, cigars, a stripper, an Italian suit, and hundreds ofdollars’ worth of Jonathan Adler coasterswithin 72 hours. Another day, a man showed up outside Duplessie’s cottage in Venice Beach on a Harley-Davidson and began loudly revving the engine and throwing rocks at the windows. Duplessie, the man shouted, owed him money.

By November 2017, James Duplessie’s career had flatlined. He’d once made up to $6 million a year; now, his income had “dropped off precipitously,” according to a lawsuit filed by his brother Michael. (They settled in 2021.) He was staying at what one friend describes as “the saddest shack in Manhattan Beach.” Over the next couple of months, the father and son hatched the idea for a new fund: Pangea, an investment firm for cryptocurrency-token start-ups. The timing was good; bitcoin and ethereum were on a frenzied bull run. Newly launched tokens were raising millions of dollars of real money based on blurry ideas that had little chance of coming to fruition. The Duplessies managed to quickly line up a pitch meeting with Jennifer Johnson, the head of Franklin Templeton, one of the country’s largest and most reputable asset managers.

It didn’t go well. “Basically every single person was rolling their eyes the entire time,” says someone who was in the room. At the time, James was dating Lucy Dahl, daughter of the author Roald Dahl. After the disastrous meeting, he began asking around about where an original golden ticket from the 1971 Willy Wonka movie, a highly valuable collector’s item, could be pawned. Within months, by April 2018, James and William Duplessie had departed California entirely.

They resettled in Switzerland. There, they quickly rebranded as a pair of successful American crypto investors, eager to help the country become a new capital for digital currency. They tried to ingratiate themselves with Swiss officials, including the mayor of Lugano, by promising to invest in local blockchain start-ups. Will began flying to bitcoin conferences in Dubai, Japan, and Singapore to sell Pangea to investors, doling out gifts along the way: cigars, $300 lighters, sometimes just cash. In mid-2018, at a conference on a yacht in Monaco, father and son ran into Roger Ver, an early crypto investor nicknamed “Bitcoin Jesus.” “James was a smooth talker who sounded trustworthy and capable,” according to someone who was there. Will, well versed in crypto and apparently on his best behavior, acted as salesman. Ver invested $2 million in Pangea, giving the Duplessies the big-name backer they needed to persuade other investors to put money in too. Soon, the Duplessiesannounced that they’d raised another $20 million in a fund overseen byCopernicus, a well-respected Swiss asset manager. They were looking for $180 million more.

That winter, cash rich, the Duplessiesmoved into a ski chalet in St. Moritz. Investors who went to the Duplessies’ parties were greeted with custom skis, armed guards, and escorts. “Those friendly women would then act as honeypots,” says an executive who watched the Duplessies solicit investors. “Potential investor hooks up with a girl, and he thinks he’s just getting lucky by association. No, no, no — that’s not what’s happening.” The money poured in, by some estimates more than $100 million. In 2020, an early crypto investor and entrepreneur sent a message to an industry-wide group chat warning others not to give or accept money from Pangea: “They’re like a train spewing cyanide in every direction, killing everything around them.”

Early that year, as the pandemic forced the world into lockdown, the Duplessies abruptly abandoned Switzerland. Many of the Swiss officials and investors they’d spent months impressing never saw them again. By 2021, investors were hounding them for their money, sending emails demanding updates. The Duplessies continued to assure Ver and other individual investors that they had huge returns coming their way soon. But the money never materialized. “They were bragging to me about it being worth some huge amount,” says one Pangea investor who has still not received the money he says he’s owed. “To be honest, I think I was scammed the whole way through.” Eventually, the Duplessies stopped joining Pangea conference calls altogether. (Pangea is in the process of liquidating whatever assets it has left. James Duplessie declined to comment on the record.)

By 2021, Will had parted with his father and moved to Miami, where he quickly racked up traffic tickets speeding down the MacArthur Causeway in expensive sports cars. He rented two houses, then abruptly stopped paying for both. (According to a lawsuit and messages from his landlord, Armen Nalband, he “trashed the place and overdosed.”) He then tried to drive a Lambo from Florida to California, but it broke down in Jacksonville. In April 2023, though his driver’s license had been suspended, he managed to crash a Porsche Cayman GTA on a Miami freeway, allegedly causing the other driver involved “disability, disfigurement, and mental anguish.”

At some point over the next few months, Duplessie returned to Switzerland. Friends later heard he spent at least part of the next year in jail there for domestic violence. This is difficult to verify — Swiss court records are sealed — but by late 2024, he was back in Miami, bragging about the new posse of tough-guy Ukrainians he’d met while locked up.

That fall, Duplessie began visiting a new friend, John Woeltz, at his home in Kentucky. The 150-acre property abutted the Ohio River in Smithland, a 200-person community four hours west of Lexington; the area was so off the grid that even locals referred to it as “the stix.”

The two made an unlikely pair. Woeltz was a mild-mannered and nerdy perfectionist with a round face and deep-set eyes; a cybersecurity obsessive, he’d begun mining bitcoin soon after its launch in 2009. By 2019, in his 30s living alone in San Francisco with his cat, he no longer had to work. “He used to live off Soylent or Huel or his own homemade vegan sludge,” said a friend. Now, back near his hometown with a net worth of over $100 million, he led a quiet life. He studied regenerative agriculture, burying the skeleton of a fish he’d caught in his garden and sending friends photos of snakes he’d shot on the property. He’d also become a patron of the small local blockchain scene, promoting statewide bitcoin-mining efforts and donating money to a start-up accelerator and co-working space in Paducah called Sprocket. It appeared to everyone who knew Woeltz that he intended to settle down and start a family with his girlfriend, Kayla Barbour, an aspiring actress and small-business owner from Lexington. Woeltz was supportive, if controlling. “In the two years we dated, I was not allowed to work and he controlled all of my finances,” Barbour would later attest. Still, they were making plans to hold a wedding in Hawaii in late 2024.

As an early bitcoiner, Woeltz had developed an online reputation as a security white hat, a kind of good-guy hacker who could easily identify vulnerabilities and to whom strangers would sometimes reach out for help — which was why, in 2020, Michael Carturan first got in touch with him. Carturan was a socially awkward permaculture enthusiast from the small Italian town of Rivoli, a technically proficient programmer who grew up on internet forums like 4chan. He believed deeply in bitcoin as a tool that could help build a new tech-focused world order and was working on a decentralized version of a virtual private network. As they got to know each other, Carturan described his expertise operating anonymous online trollbots and “running psyops” — in other words, using social-media bots to hype meme-coin projects, making them appear more popular than they actually were. In the beginning, he was reluctant to give his real name, introducing himself only as “Sergio.” “It was always some made-up Italian name,” says a mutual friend. Soon, the two were collaborating on a brand-new cryptocurrency project. Over the years, Carturan came to see Woeltz not just as a business partner but as a role model and protector. When Carturan worried a former colleague was trying to kill him over a business dispute, he asked Woeltz for help. “John saved my life,” he would later tell others.

Carturan knew Duplessie, too — Pangea had invested in his cryptocurrency project in 2021. And it was through Carturan that Duplessie and Woeltz eventually developed their own relationship. By December 2024, Duplessie could almost always be found at Woeltz’s Smithland cabin. “John and Will began displaying very paranoid, cultlike behavior,” Barbour later wrote in a restraining-order petition against Woeltz. His demeanor had shifted dramatically; he and Duplessie bought thousands of dollars’ worth of guns and “began wearing matching militant clothes,” patrolling the property “on the hunt for terrorists who they were convinced would be tracking us down to kill us.”

By January, Woeltz’s relationship with Barbour had reached a boiling point. At dinner one night, Woeltz demanded that she load his magazine clip for him, according to court documents. She refused. “Load the gun or get out,” Woeltz said. Then he grabbed her by the throat and put the gun to her head, “screaming that he was going to kill me and that he had a hole dug to bury me in,” she said. Woeltz and Duplessie locked her in her bedroom, took her phone, “and refused to allow me to leave the bedroom for several hours.” She wasn’t let out until the next morning. By then, a snowstorm had set in, trapping her in the home with the two men for another week. After the weather cleared, the group went out for Chinese food. Woeltz lashed out, asking Barbour why she’d taken them to “that Chink restaurant with spies.” “You should have cooked me dinner and sucked my dick,” he said. The next day, Barbour checked herself into a rehabilitation center in Arizona.

After rehab, Barbour returned to her mother’s home in Lexington. She and Woeltz had broken up, and a relative went to check on her car at his house. They found the Mazda riddled with bullet holes, its windows completely blown out. Barbour filed a police report and a restraining order. “My ex-partner has unlimited resources,” she wrote in her petition to the court, part of an ongoing domestic-violence case. “I am afraid this person is extremely unhinged and severely mentally ill — and completely unpredictable as he reacts violently in fits of rage. He is armed and dangerous.”

Barbour’s departure meant one less check on Woeltz and Duplessie’s activities, which took on a new level of organization. With Duplessie’s father, they formed a venture they called Wildcat. The plan was apparently to buy up land and distressed assets in Kentucky. To help with this, they hired Scott Hernandez, a New York–based real-estate investor who had formerly worked with Jeb Bush. Hernandez, the son of wealthy Republicans, also advised Duplessie on his political aspirations. Duplessie wanted to run as a candidate for Mitch McConnell’s Senate seat. Hernandez brokered a meeting with the campaign manager for Nikki Haley’s presidential run.

That winter, holed up on Woeltz’s estate, he and Duplessie typed out what prosecutors would later call a manifesto. The plan, as they laid it out, was to steal foreigners’ cryptocurrency through an “intelligence operation.” The document included a list of targets. Woeltz and Duplessie would slowly gain “their trust over a long period of time while also investigating them, discovering their intents and networks, as well as any other valuables,” they wrote. Then they’d strike. “We will take bitcoin and crypto from evil people. This agency will actively purge America of its bad foreign powerhouses. Crypto keeps them alive because it is off the grid. It is our belief that these people need to lose their coin.” They mentioned three targets, including Michael Mauer, the German-born CEO of a security company called Blockfinance ECO AG, based in Liechtenstein, who had worked with Woeltz years earlier. They also mentioned Carturan, their Italian business partner and friend.

In January, Duplessie decided to officially move to Kentucky. Through their shared LLC, Mr Smith, the two purchased the most expensive home in Smithland, a 10,000-square-foot riverside mansion known locally as the Smith Mansion, built to resemble the White House. When they showed up to collect the keys, they were dressed in full body armor, driving a camouflage Apocalypse Hellfire, carrying guns, and accompanied by a cadre of guards. They told the former owners they’d been hunting coyotes, despite the fact that it was the middle of the day. They’d barely been in the house a week when the Livingston County sheriff’s office received a strange call from a local Holiday Inn. The front-desk clerk reported their guest — an older woman with a thick German accent — had received an alarming text from her son. He had gone to spend time with his friend John but was being held for ransom, he’d told her, and his captors were “armed to the brim.” They weren’t letting him leave; he asked his mother to send them half his cryptocurrency. Nearly an hour later, the man — identified as Michael Mauer — called his mother from the street, a few blocks from the mansion. His captors had apparently let him go. When officers arrived, they found blackout shells, remnants of bullets that could be used with a suppressor or silencer, scattered “all over the front yard.”

From left: Inside the Smith Mansiontypewriters set up in the Smith Mansion dining room

From top: Inside the Smith Mansiontypewriters set up in the Smith Mansion dining room

That same winter, Duplessie went to visit Peter Brant Jr., whom he’d kept touch with in the years since Bard, in Palm Beach. He asked his well-connected friend if he would introduce him and Woeltz to influential people on the local scene. Brant set up a dinner with a few friends, including one who had recently launched a business, which Duplessie expressed interest in investing in. The dinner went well — Duplessie and Woeltz came off as “your typical nerds, very quiet,” according to someone who was there — and a couple days later, the whole group plus a few other friends boarded a private jet to Kentucky. As soon as the jet took off, Woeltz and Duplessie started “talking about probably the most insane shit I’ve ever heard in my fucking life,” someone who took the trip says. Duplessie said that he’d been a participant in MKUltra, the secretive military experiment on psychedelics that ended decades before he was born, and that he was a CIA operative who was “found at a very early age.” Then the conversation turned to a “German terrorist” he and Woeltz had recently encountered on their property. Duplessie said they had to “take him out to the farmhouse” and “keep him there for about six weeks.” Then, he said, they “took all his crypto to defend the front lines of America” and “got rid of him.”

When they arrived at the Smith Mansion, Duplessie offered everyone military-style fatigues to change into. There were no computers in the house, he informed the group. Instead, they used typewriters to communicate. He gestured to a grand dining-room table covered with dozens of them. Then Duplessie and Woeltz “sat around typewriting messages to each other, then lighting them on fire so nobody could see what they were talking about because they work for the CIA,” the guest says. As their guests nervously settled in, Duplessie and Woeltz wandered around, pistols holstered on their hips. Over their shoulders, they wore AR-15’s with 100-round drums, fully loaded, with no safety on. Later that night, Duplessie pulled a Buck knife out of his camo vest and used it to slice open a Ziploc bag full of cocaine.

By the next afternoon, Duplessie, high and armed, seemed even more unmoored. The house chef had apparently given one of the guests a pill that made her fall asleep, and Duplessie exploded: He pulled out a pistol, cocked it, and held it to the chef’s head. “Now you’re gonna play Russian roulette, like last time,” he told him. After the guests protested, Duplessie amended the punishment, instead forcing the chef to change into a cartoonish outfit and bake the group a cake. At the end of the weekend, the group boarded the plane back to New York. Woeltz and Duplessie decided to come along. They had business there, they said. A few weeks later, they moved into 38 Prince.

The townhouse, an eight-bedroom with double-high windows that look out on St. Patrick’s Basilica, cost $75,000 a month. Before they moved in, Duplessie and Woeltz had to submit personal bios and pass background checks; the landlord readily accepted their application. They soon made the space their own. In came a staffed coat-check room, bartenders, and teams of security guards, some of whom had day jobs working for the NYPD. Duplessie moved a professional DJ setup and sound system into the basement. Piles of cocaine were procured, along with a silver Tiffany tray to serve it on. Brant was consulted to curate a selection of contemporary art and furniture.

To ferry in guests, Duplessie and Woeltz relied on their new assistant, Morgan O’Connor, a well-connected club rat and former model known for his striking look: white with waist-length dreadlocks. O’Connor seemed to know every bottle girl in the city, and he soon brought on Charlie Zakkour, a handsome 30-year-old starring on Bravo’s Real Housewives spin-off Next Gen. The pair grew up together on the Manhattan party circuit; both briefly dated Lindsay Lohan as teenagers. They set to work finding young women to party with Woeltz and Duplessie. “They’re gonna drop stupid money — like, life-changing amounts of money,” Zakkour told a friend about his new job. “They’re ready to spend.” There was an unusual source to help stock the parties at 38 Prince: the Soho location of Brandy Melville on nearby Broadway. The clothing shop is known for employing attractive young women, many of them part-time models. Zakkour had dated several of them over the years and often brought them and their friends to clubs and after-parties. (Sometimes he’d drop by the store just to hang out, leading one young employee to ask herself, “What’s an unc doing at Brandy?”) Duplessie and Woeltz were thrilled to be around young women. “They love the Brandy girls,” said one promoter. “They were very keen on having a ton of chicks with them at all times for just, like, motion.”

Duplessie was a generous host. At a party in March, he gave five figures in cryptocurrency to one young woman, then another five figures to her friend, just for showing up. They let young women order themselves dinner on their accounts from Blue Ribbon Sushi. But sometimes the generosity was more transactional. Duplessie told women he would pay them to “bring hot bitches over,” sometimes offering as much as $20,000. Other women he slept with received designer bags and shoes. He could be charming, and the debaucherous atmosphere he cultivated could feel romantic in a transgressive way. “Every girl who went to that house thought she was Lana Del Rey,” said one guest.

Other times, the mood felt more like Kentucky. Duplessie and Woeltz would roam the house in night-vision goggles and show off the loaded gun and small chain saw they kept in the house. Duplessie sometimes described violent fantasies of revenge against terrorists, his exes’ new lovers, or other perceived enemies. Once, Woeltz injured Zakkour’s nose by accidentally headbutting him. Another time, he snipped off one of O’Connor’s dreadlocks while his back was turned. (O’Connor did not respond to requests for comment.) He could be hostile. “He was looking at these girls, and he’d be like, ‘Look at that. That’s a slut right there. They just want my money,’” one acquaintance recalls. He’d talk about how he was a crypto vigilante, wanted in Russia and China, and show people photos of Barbour’s blown-out car, which he used as his phone background.

Woeltz often didn’t stick around for the parties at all. Instead, he’d retreat to his room on the fourth floor, sit at his computer, chain-smoke Marlboros, and blast dubstep. He’d complain that he didn’t even like New York, or nightclubs, or the Louis Vuitton pajamas Duplessie made him wear. He just wanted to settle down in the countryside and have a family.

Though they were busy partying, they apparently hadn’t stopped iterating on the plan they’d laid out in their manifesto back in Kentucky. Soon after they arrived in the city, they pitched a potential recruit for their project, a former bitcoin thief turned start-up founder, on moving into 38 Prince and joining what they’d described as a “team.” They were vague about what they wanted him to do. Their work was top secret, Woeltz explained, but they did tell him they were building a SCIF — a “sensitive compartmented information facility,” or a room designed to store classified data — at 38 Prince, along with a Faraday cage, an area shielded from radio signals. Over a $10,000 dinner at Raoul’s, Woeltz gave the recruit a peek at his phone, which he was using to remotely control a desktop computer on which he was running a program called Hashcat. The recruit knew all about Hashcat, a password-cracking program sometimes used to steal crypto: “I pretty much knew instantly at that point that he was up to something because nine out of ten times when somebody is using that, it is for a nefarious reason.” Later that night, Duplessie texted him a selfie wearing night-vision goggles and military garb. “I run the internet,” Woeltz added.

Eventually, Duplessie and Woeltz told the potential recruit that in order to work with him, they’d have to vet all of his finances and do a “full-scope background check.” This would entail handing over control of all of his cryptocurrency wallets. His crypto, they told him, was “Chinked,” or corrupted. The Chinese were chasing them, they said, trying to find them and kill them because of their work stealing bitcoin from foreign enemies on behalf of the government. In order to “un-Chink” his cryptocurrency, or clean it, Duplessie and Woeltz said they would have to take control of it. The recruit, feeling suspicious, turned down the job.

If their cover story — that they were undercover agents stealing bitcoin from terrorists, pedophiles, and “evil people” on behalf of the CIA and NSA — seemed far-fetched, their alleged scheme itself was fairly straightforward. As they wrote in their manifesto, they planned to take bitcoin and crypto. Bitcoin is just 16 years old, and we are only now seeing the maturation of a robust and significant crypto crime business. “Rug pulls” and meme-coin pump-and-dumps are quintessential and now-familiar hustles that anyone with a decent PR strategy could pull off.

But the sinister characters who have recently entered the picture, targeting especially wealthy crypto holders, are more unnerving to crypto evangelists: Investors may tolerate a little light fraud in service of the larger project, but no one expects to be tortured. In France, a crypto-wallet start-up CEO had his finger sawed off by attackers who demanded ransom money; in England, an investor was held at gunpoint. Similar incidents — now called “wrench attacks” — have taken place in Germany, Canada, Japan, Korea, and Uganda. In response, the French minister of the interior recently announced a raft of measures — specialized training for police focused on “anti–crypto asset money laundering,” a new working group to improve techniques for tracing crypto assets, and security training to educate individuals on best practices. Investors have had to rethink travel plans, their digital footprint, and the conferences they attend, especially after a recent data leak from the trading platform Coinbase released what is essentially a list of potential targets.

Typically, people keep their bitcoin and ethereum either in virtual wallets like MetaMask or in a “cold wallet,” a physical device unconnected to the internet. (Many sophisticated investors will keep the majority of their holdings in the latter.) If someone obtains the password to a virtual wallet, or gets their hands on a physical wallet along with its “private key,” they can transfer all of the money into their own account. Crypto’s nouveau riche, like Carturan, are essentially walking around with millions of dollars in their pocket. It’s not that crypto is untraceable. Transactions are recorded permanently on the blockchain, giving investigators a thread to follow. But there is not always a bank to reverse a fraudulent transaction. In this sense, crypto is closer to gold. In real terms, protection is only as strong as an investor’s ability to conceal their password.

Duplessie and Woeltz’s alleged tactics have struck some as especially extreme. “It’s basically my worst nightmare to meet up with someone I know from the industry and they try to torture me for my private keys,” says one founder of a blockchain protocol. The increasing violence in the world of digital currency has put crypto whales in a bind. To hold their coins, they must harden their lives with constant security or try to become anonymous ghosts, unable to flaunt their wealth, lest trusted partners dox or betray them.

This April, Woeltz and Duplessie reached out to Carturan. They were launching a new fund, they said, and wondered if he wanted to come work on it. They also offered him something else: a sort of self-improvement program, which would help him in his efforts to become tougher and more “macho.” Carturan told the pair his sheltered youth in small-town Italy had left him unprepared for the dangers of crypto’s increasingly violent Wild West. After Carturan said his former colleague had threatened his life, Duplessie had urged him to begin strength and combat training. The April move to 38 Prince would be the next phase of this life upgrade. Later, prosecutors would say there was a more urgent motive behind Carturan’s transatlantic trip. Months earlier, while he was staying with them, Duplessie and Woeltz had confiscated devices from Carturan containing crypto reportedly worth $30 million. They insisted he move in with them if he wanted to get them back.

When Carturan first moved into the house, he seemed, to outsiders at least, to be enjoying himself. Duplessie and Woeltz gave him a large room on the ground floor with its own en suite bathroom. He was a regular at their parties, where Duplessie and Woeltz sometimes introduced him as their business partner, or intern, or “Hogleg,” their nickname for him, inspired by the size of his penis. O’Connor told someone he seemed more like a fraternity pledge. They dolled him up in outfits, including dresses and a collar from Agent Provocateur that Duplessie had originally bought for his girlfriend. One night, it was tiny shorts, a crop top, and a lampshade on his head; another, it was a Buc-ee’s beaver costume. In a video from April, Carturan and his hosts are stopped by a street-style content creator who goes by Preppy Pete after a shopping spree at the Rick Owens store. As Pete marvels at Carturan’s new drapey, sheer clothing, Duplessie laughs: “There’s not a single funnier thing that could have just happened!”

Carturan served drinks at parties, did push-ups, carried a rug up and down the street, and played Edward Fortyhands, a drinking game wherein two bottles of malt liquor are bound to the palms. Prosecutors later alleged that they put him in a cage in the kitchen. A 19-year-old Brandy employee asked Carturan why he was doing all of this. “It makes me stronger,” he told her. Besides, the residents of 38 Prince showed at least some concern for Carturan’s well-being. One night, the group was horsing around with a whip from a sex store. “I accidentally hit Michael too hard with it, to the point where he audibly said, like, ‘Ow, ow,’” the Brandy employee said. “Everyone in the room stopped and was like, ‘Hold on, that’s not funny.’” She apologized to Carturan, and “five minutes later, we were all dancing and, like, having fun again. It just seemed cheerful and lighthearted.”

Adding to this impression was Carturan’s seemingly enthusiastic consumption of drugs — including crack that he and Duplessie cooked in an air fryer — and his pursuit of the women around him. According to court documents and videos, he participated in a variety of sexual escapades at the townhouse, including orgies and BDSM. In one video, he lies on his back as a nude woman bounces up and down on his face. Much of what he had to say at parties revolved around women. “He would talk a lot about, like, ‘Oh yeah, that girl had big boobs,’” the 19-year-old recalled. “Or, ‘That girl was chopped.’” In court, he later said that both his drug use and the sex were under duress. He was afraid of Duplessie and Woeltz, so he tried his best to fit in with the alpha-male environment they fostered and to withstand his hazing with a brave face. He was afraid of what might happen if he didn’t, prosecutors said. Duplessie and Woeltz always told him not to show fear, he said, and to be a man. He testified that while he was staying at 38 Prince, his hosts began pressuring him to divulge the passwords to his accounts and insisting that he provide them with yet more devices containing crypto. If he didn’t follow orders, they said, he would be a terrorist. And he knew what they did to terrorists: Hunt them down. He believed they were undercover agents with a license to kill. Plus Carturan wasn’t the type to seek out police attention. Over the years, he’d managed to almost completely hide his digital footprint; he hadn’t even used his real name with his former colleagues or, at first, with Woeltz. And so he resisted divulging his passwords, even as he feared for his life and his family’s. (Carturan didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.)

Over the course of May, Duplessie and Woeltz became more focused on gaining access to Carturan’s cryptocurrency, according to court documents. Carturan briefly returned to Italy at the end of April — on orders from Woeltz and Duplessie, he testified, who wanted him to retrieve yet more crypto wallets — and when he returned in the first week of May, his hosts took his passport, he said. Their assistants were assigned to monitor his whereabouts and let him go for walks or to the gym only with permission. At some point, they made him wear a collar with an AirTag in it. He was allegedly not allowed to keep his phone and even had to ask permission to use it, Duplessie and Woeltz said, because he was a terrorist. In May, Duplessie joked with a friend about upping his own drug intake to keep up with what they were giving to Carturan; he went so far as to make custom tank tops screenprinted with an image of Carturan smoking a crack pipe. In a video taken on May 15, Carturan stands in an empty closet, his hands hooked through some hangers. He’s wearing one of the shirts; so is the 19-year-old Brandy employee, who stands in front of him holding a cattle prod. “One more time,” she says, shocking him in the midsection. Carturan screams as he collapses to the floor. “You didn’t get hit,” she says. “No, I did get fucking hit,” he tells her, before Duplessie walks over to give Carturan a high five.

In another video, Carturan is sitting on the floor, wearing a hoodie, when someone comes up and ignites a small blue flame on his back. He jumps up and frantically puts it out against a wall. In court, defense lawyers called this incident a prank, like when baseball players light one another’s shoes on fire in the dugout. But, prosecutors later said, Carturan disagreed. They described disturbing punishments meted out to him by Duplessie and Woeltz: cutting him with a chain saw and cauterizing the wound with a flame, holding him over the edge of a staircase four floors up, holding a gun to his head. Through it all, Carturan never provided them with his crypto log-ins, he’d testify.

It finally came to an end on May 22, Woeltz’s birthday. According to friends, the group threw him a “China”themed party — given his long-standing obsession with the country — and that night, everyone wore kimonos and rice-paddy hats and headed out to dinner at Sartiano’s. Woeltz was in a terrible mood. He complained to attendees that he despised his birthday. After dinner, the group went to Little Sister, a club on East 11th Street, where Woeltz’s credit card was declined. Embarrassed, he sent a security guard back to 38 Prince to get a new one. By 4 a.m., back at the house, he was belligerent, stomping around the top floor and ranting incoherently. He smashed a vase against a wall. A woman Woeltz had been casually dating was so afraid that she hid and called Zakkour. Woeltz, she told him, was out of control.

In the early morning hours, Duplessie walked in on Woeltz screaming at Carturan, who was bleeding from his head. Duplessie tried to calm Woeltz down but eventually decided to leave, collecting two girls who were in the house and retreating to the Mercer Hotel. A few hours later, just after 9:30 a.m., Carturan dashed out of the house and, videos show, down the block to a traffic cop on the corner of Mulberry Street. At first, he told cops that he’d been hazed. “I wanted to work with them, so they were making me tougher.” But then he elaborated: Woeltz, he said, “was mad at me because I caused a breakup with his girlfriend. He was going to kill me. He hit me with a gun and that’s why I ran out.” Woeltz had then loaded the gun, Carturan said. Then Woeltz told him, “This is the day you will turn over the crypto.”

From left: Duplessie being escorted from the police precinct. Photo: Jefferson Siegel/The New York Times/ReduxJohn Woeltz in custody outside the townhouse. Photo: Kava Gorna/AP

From top: Duplessie being escorted from the police precinct. Photo: Jefferson Siegel/The New York Times/ReduxJohn Woeltz in custody outside the townho…

From top: Duplessie being escorted from the police precinct. Photo: Jefferson Siegel/The New York Times/ReduxJohn Woeltz in custody outside the townhouse. Photo: Kava Gorna/AP

At their State Supreme Court arraignment.

Photo: Jefferson Siegel/The New York Times/Redux

Zakkour arrived just in time to see Woeltz emerging from the front door, handcuffed and in a white bathrobe. When police searched the house, they found blood in the areas of the apartment where Carturan said he’d been tortured, according to court records, as well as Polaroids of Duplessie and Woeltz holding a chain saw against his leg and a loaded gun to his head. They found tarps, buckets, goggles, and a hacksaw, which Carturan claimed Duplessie and Woeltz had threatened to use to dispose of his body. They also found three documents, presumably drawn up by Duplessie and Woeltz, purporting to charge Carturan with violations of the Patriot Act and Italian law. Those included sections for him to provide the passwords for his cryptocurrency wallets. Carturan’s account shocked those who had spent time at the house and thought he’d been having fun. “It was like D-Day in the Brandy store,” says a friend of several employees. Multiple girls were in tears, frightened they’d accidentally become accessories to torture. One said that the experience had “caused a flare-up” of her “crippling anxiety and panic disorder.”

Duplessie quickly decamped to the Hamptons for Memorial Day weekend, negotiating his own surrender to the police even as he partied at clubs. He called the Realtor for the Smith Mansion. He needed the house sold, he told her, “ASAP.” It was too late. On June 10, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives raided both the Smith Mansion and Woeltz’s cabin. They seized five guns, according to the ATF, and more than 2,000 rounds of ammunition. (James Duplessie’s Coral Gables home was later raided too; agents seized a Glock pistol.) On June 11, Duplessie and Woeltz were arraigned on charges of first-degree kidnapping, a crime that carries a sentence of up to life in prison, as well as assault, coercion, attempted grand larceny, and criminal possession of a weapon. Their lawyers have argued that Carturan exaggerated his plight. He could not have been kidnapped, they said, if he was free to come and go from 38 Prince. Plus, in the video evidence, he’s “all smiles.” In response, prosecutors brought out texts in which Woeltz talked about “torturing” Carturan, as well as messages between assistants who described Carturan sobbing, hyperventilating, and appearing “broken” with “no more life in his eyes.”

The evidence raises complicated questions. The prosecution claims that Carturan was a captive for 17 days, from May 6 through 23. Prosecutors must convince a jury that he was only pretending to enjoy himself during that period; that he was having sex, taking drugs, and going to clubs just to placate his captors. It doesn’t seem that he was chained up in the basement. He left the house numerous times, including the night before Woeltz was arrested. Why did he wait almost three weeks to flee if he was allegedly being tortured? And why did he tell multiple people he was merely being hazed — including when speaking to the police shortly after Woeltz’s arrest? Prosecutors have placed Woeltz’s net worth at more than $100 million, and Carturan’s has been reported at $30 million. What sort of thief robs people with far less money? The defense, meanwhile, must argue that the mountain of bizarre and terrifying things the police found — cattle prod, cage, wheelchair, crack, chain saw, loaded gun, threatening Polaroids, blood, corpse-disposal implements, fake legal documents, crypto-theft manifesto — was all just window dressing for a sequence of harebrained pranks that Carturan signed up for, until one night he decided it had all gone too far, leading him to concoct a story that reframed his hazing as torture. (A lawyer for Duplessie declined to comment. A lawyer for Woeltz did not respond to requests for comment.)

So far, the two have been charged only in Manhattan criminal court; Kentucky state police opened a probe early this year, while the Feds, including the ATF, continue their own investigation. “None of it surprised me about having that kid come over and partying with him, and convincing him this was fun while you were maybe also torturing him, or playing head games with him,” says a former Duplessie associate who has known him for almost a decade. “ ‘Oh, it’s all in good fun.’ And then the next thing you know, it’s not in fun — that’s very much Will’s style. He’s just a guy who should be in jail.”

In mid-July, Woeltz and Duplessie were granted bail, though only Woeltz has been released. He’s still adjusting to the radical shift his life has just undergone. “I don’t understand why I’m here,” he told officers the morning of his arrest. “I’m from Kentucky. I came out here for work. Obviously, it’s going great. Hedge fund. I’m 37. My birthday was yesterday. We went out to a club for a little bit. We had a few drinks. It was all right. New York has not the best reputation in Kentucky, but everyone here has been really, really good.”